Modernism is an expansive and intricate cultural, intellectual, and artistic movement that emerged during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It represents one of the most significant shifts in human creativity and thought, challenging established norms and redefining the very essence of art, literature, and society. Born out of profound societal changes, Modernism continues to influence contemporary culture and thought, making it a critical area of study for understanding the evolution of modernity.

Origins and Influences

The roots of Modernism are deeply embedded in the transformative developments of the 19th century. The Industrial Revolution reshaped economies and societies, replacing agrarian lifestyles with mechanized urban centers. This rapid industrialization brought about profound changes in human experiences, including new social structures, increased mobility, and the alienation of individuals from traditional communities. The pace of life quickened, and cities grew into bustling hubs of activity, often marked by stark contrasts between progress and poverty.

These shifts set the stage for a reevaluation of traditional forms of art, thought, and expression. Philosophical and scientific revolutions further fueled this transformation. Friedrich Nietzsche’s radical declaration that “God is dead” questioned the foundation of Western morality, urging humanity to forge new paths of meaning. Sigmund Freud’s exploration of the unconscious mind opened new dimensions of human psychology, influencing how individuals understood themselves and their emotions. Meanwhile, Karl Marx’s critique of capitalism laid bare the structural inequalities of industrialized societies, calling for revolutionary change.

Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, introduced in On the Origin of Species (1859), challenged religious and scientific understandings of humanity’s place in the natural order. These intellectual breakthroughs collectively created a fertile ground for Modernism, inspiring artists, writers, and thinkers to break away from established conventions and engage with the complexities of modern existence.

Key Figures

Modernism was propelled by a diverse array of visionary individuals who contributed to its rich tapestry across disciplines:

- Literature: James Joyce, a pioneer of stream-of-consciousness narrative, transformed storytelling with works like Ulysses (1922), capturing the inner workings of the human mind. Virginia Woolf explored themes of gender, identity, and perception in novels such as Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse. T.S. Eliot’s poetry, particularly The Waste Land (1922), encapsulated the existential despair and fragmentation of the post-World War I era.

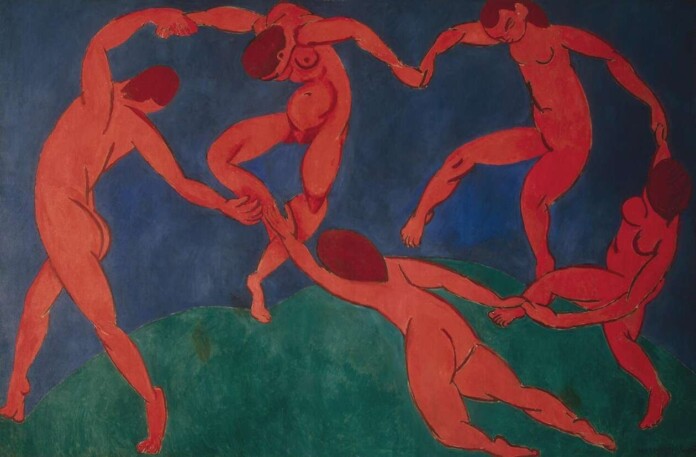

- Visual Arts: Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque led the charge in Cubism, deconstructing objects into abstract forms that challenged perceptions of reality. Henri Matisse’s use of vibrant colors and bold shapes revolutionized artistic expression. Wassily Kandinsky, a pioneer of abstract art, sought to convey spiritual themes through non-representational forms.

- Architecture: Le Corbusier’s principles of urban planning emphasized functionality and simplicity, influencing modern cityscapes. Frank Lloyd Wright’s organic architecture integrated buildings with their natural surroundings, exemplified by masterpieces like Fallingwater.

- Music: Composers such as Igor Stravinsky, with his groundbreaking The Rite of Spring (1913), and Arnold Schoenberg, who developed the twelve-tone technique, broke away from traditional harmonic structures. Claude Debussy’s impressionistic compositions evoked mood and atmosphere in innovative ways.

- Theater: Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot epitomized Modernist theater, exploring existential themes through minimalist settings and dialogue. Bertolt Brecht’s epic theater invited audiences to critically engage with societal issues.

Major Artistic Movements

Modernism was not a singular movement but rather a constellation of overlapping artistic currents, each contributing to its overarching ethos:

- Impressionism: In the late 19th century, artists like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas sought to capture fleeting moments and the effects of light and color, moving away from realistic depictions.

- Cubism: Initiated by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, Cubism fragmented objects into geometric shapes, offering multiple perspectives within a single composition.

- Futurism: Rooted in Italy, Futurism celebrated speed, technology, and industrial progress, with artists like Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Umberto Boccioni leading the charge.

- Surrealism: Inspired by Freudian psychoanalysis, Surrealism delved into the unconscious, producing dreamlike and fantastical imagery. Figures like Salvador Dalí and André Breton redefined the boundaries of artistic imagination.

- Expressionism: This movement, exemplified by Edvard Munch and Egon Schiele, emphasized emotional intensity, often portraying existential angst and inner turmoil.

These movements collectively challenged traditional definitions of art, encouraging experimentation and new ways of seeing the world.

Regional Variants

Modernism’s impact was global, adapting to local contexts and cultures:

- Europe: Paris emerged as the epicenter of Modernist creativity, attracting a cosmopolitan community of artists and intellectuals. Vienna fostered innovations in architecture, psychoanalysis, and music, while Russian Constructivism merged Modernist aesthetics with the ideals of the Bolshevik Revolution.

- United States: The Harlem Renaissance was a uniquely American manifestation of Modernism, blending African American cultural traditions with contemporary themes. Writers like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston and musicians like Duke Ellington reshaped American art and identity.

- Latin America: Modernism in Latin America reflected the region’s complex history and identity. Frida Kahlo’s deeply personal paintings and Diego Rivera’s politically charged murals exemplified a fusion of indigenous heritage and global Modernist trends.

- Asia and Africa: Modernist movements in these regions often grappled with colonial legacies and modernization. In Japan, architects like Tōgo Murano blended Modernist principles with traditional aesthetics. African artists and writers used Modernist techniques to assert cultural identity and critique colonialism.

Artistic and Literary Movements

Modernist literature pushed the boundaries of narrative form and language. Stream-of-consciousness techniques, as pioneered by Joyce and Woolf, mirrored the fragmented nature of thought and perception. Poets like Ezra Pound championed imagism, emphasizing precision and economy of language, while Wallace Stevens explored philosophical themes through richly layered verse.

In the visual arts, abstraction became a hallmark of Modernism. Movements like Cubism and Surrealism dismantled traditional artistic conventions, offering innovative approaches to composition and meaning. These developments encouraged viewers to actively engage with art, interpreting its multiple layers and meanings.

Architecture and Design

Modernist architecture sought to harmonize functionality with aesthetics. The Bauhaus school, founded by Walter Gropius, integrated art, craft, and industry, influencing design worldwide. Iconic structures like Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye and Mies van der Rohe’s minimalist skyscrapers exemplified Modernism’s emphasis on simplicity and utility.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s organic architecture, blending buildings with their environments, provided a counterpoint to urban Modernism. His designs, such as the Guggenheim Museum in New York, remain enduring symbols of architectural innovation.

Music and Performance

Modernist music broke with traditional tonality, embracing dissonance and experimentation. Arnold Schoenberg’s twelve-tone system and Igor Stravinsky’s rhythmic complexities expanded the expressive possibilities of music.

Theater also evolved, with playwrights like Brecht and Beckett rejecting conventional narratives in favor of abstraction and existential inquiry. These innovations redefined the relationship between performers and audiences, making theater an active site of engagement and reflection.

The Legacy of Modernism

Modernism’s influence peaked in the mid-20th century but continues to shape contemporary culture. Postmodernism, which emerged as a critique of Modernism, both extends and challenges its principles, emphasizing plurality and questioning grand narratives.

Modernism remains a defining moment in cultural history, reflecting humanity’s capacity for reinvention and innovation. Its legacy endures in art, literature, architecture, and beyond, inspiring ongoing exploration of the complexities of modern life.

Conclusion

In essence, Modernism was more than a cultural movement; it was a profound transformation of human perspective in response to the rapid changes of its time. It compelled individuals to rethink identity, purpose, and the essence of creativity in a rapidly evolving world. Its myriad manifestations—from abstract art to experimental literature and radical architectural designs—demonstrate the resilience and adaptability of human ingenuity.

Modernism’s insistence on breaking free from tradition has left an indelible mark on global culture, prompting future generations to continue questioning, innovating, and reimagining. By embracing the complexities and contradictions of the modern age, Modernism opened doors to new realms of expression and understanding, ensuring its relevance and influence for centuries to come. The movement not only shaped the 20th century but also provided the foundation for ongoing debates about the relationship between tradition, innovation, and the human experience.

in Bahia.

in Bahia.