Stephanie Shih, long celebrated for her trompe l’oeil ceramics that mimic pantry staples and objects associated with domestic life, is building on that foundation in powerful new ways. In two concurrent exhibitions, she weaves mosaic, pottery shards, and glass fragments into artistic compositions that probe labor, identity, and cultural lineage. Her shift into mosaic isn’t mere decoration — it is a deep engagement with craft, memory, and the often-hidden hands that shape everyday items.

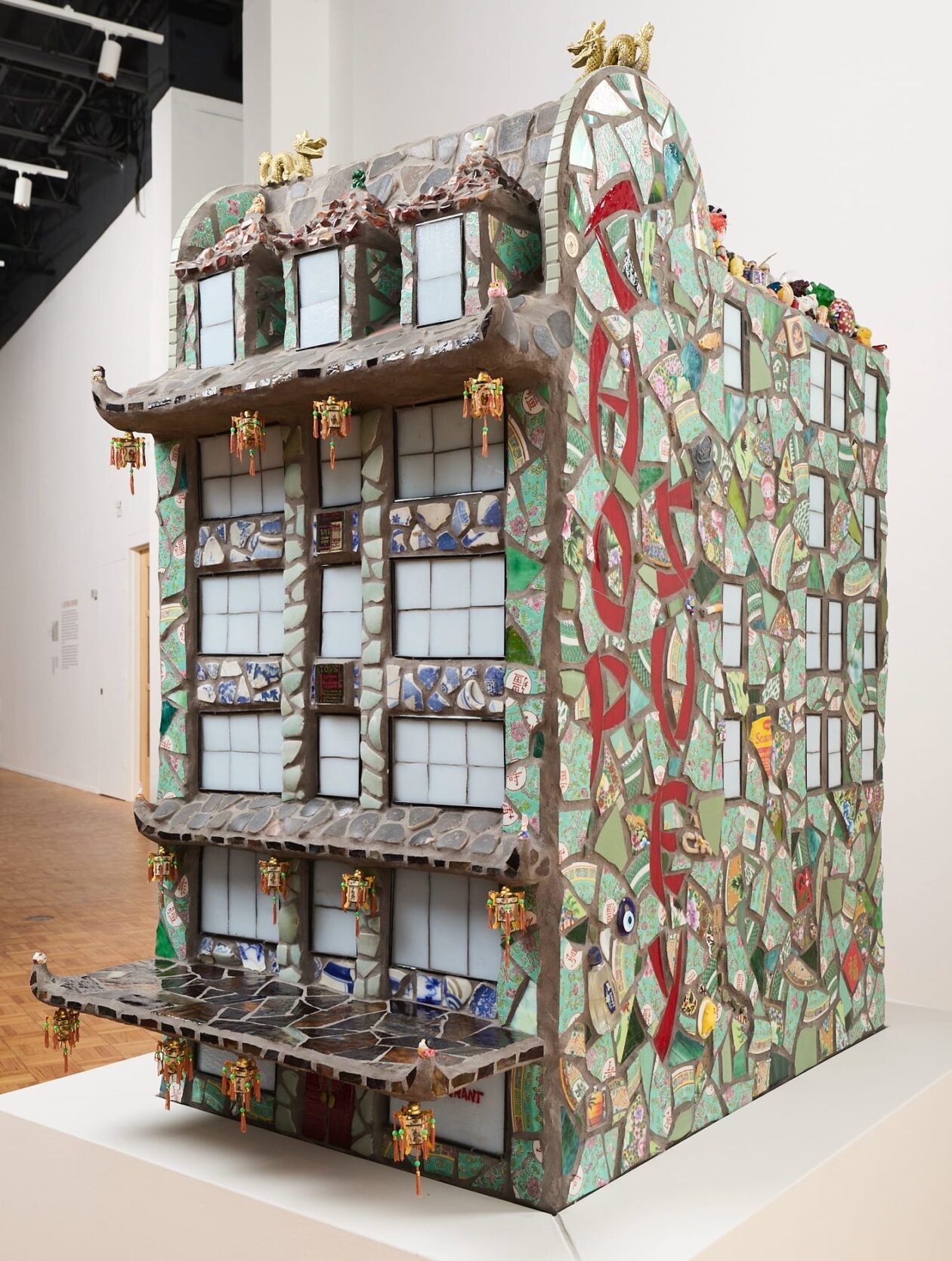

At the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, Shih presents Toy Building (1915–1939), a six-story structure styled like a pagoda. Its facade is dressed in broken porcelain dinnerware, polished stone, and ceramic shards recovered from a Chinese fishing village on Monterey Bay. Along the rooftop and outer surfaces, hundreds of found and crowd-sourced knick-knacks and figurines cluster, creating a layered visual texture that traces histories of migration and community building.

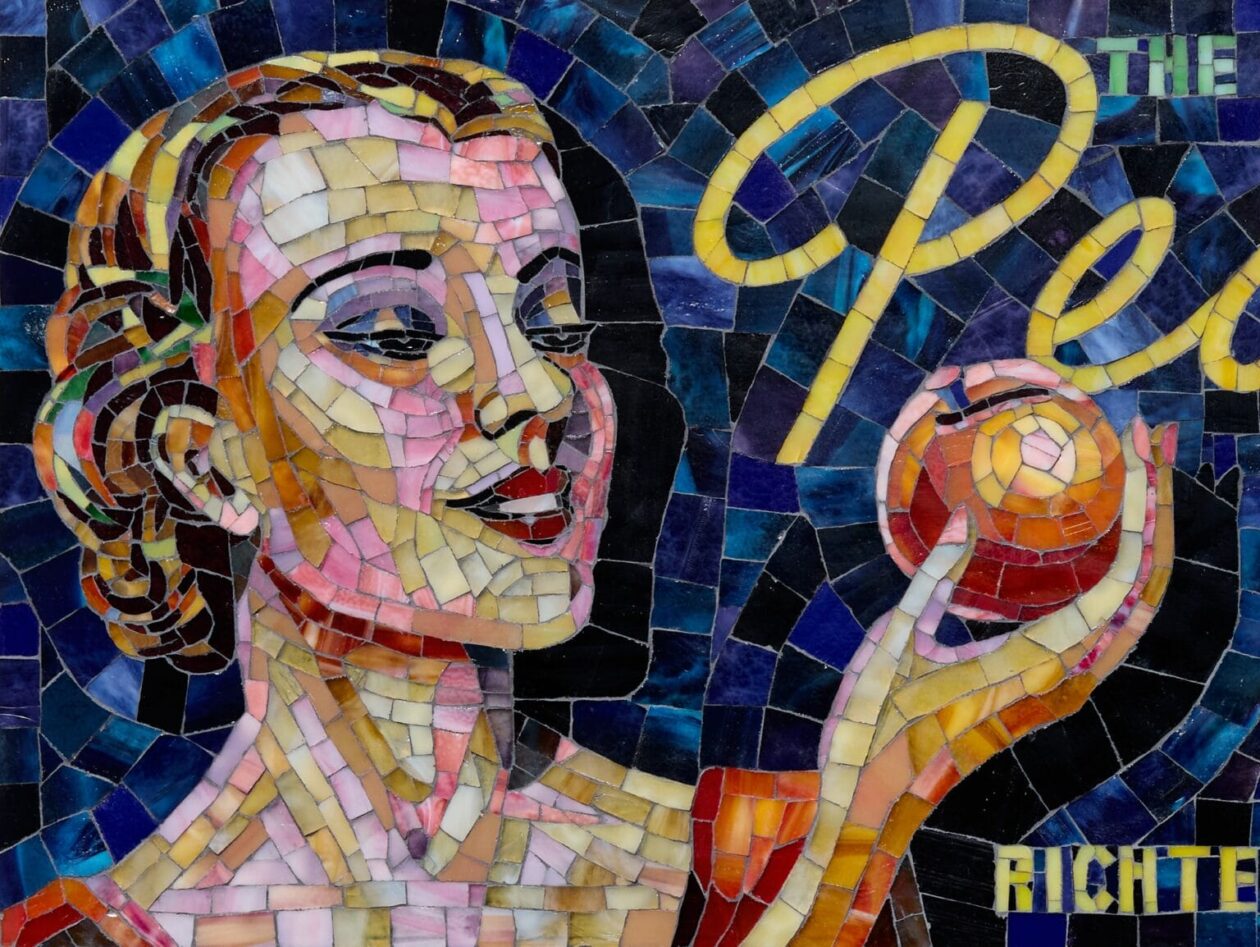

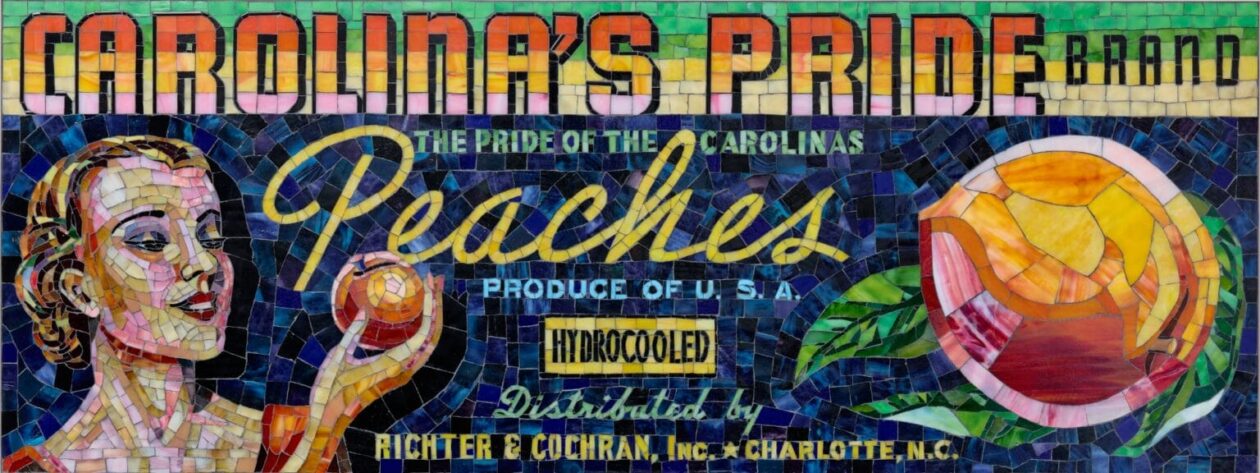

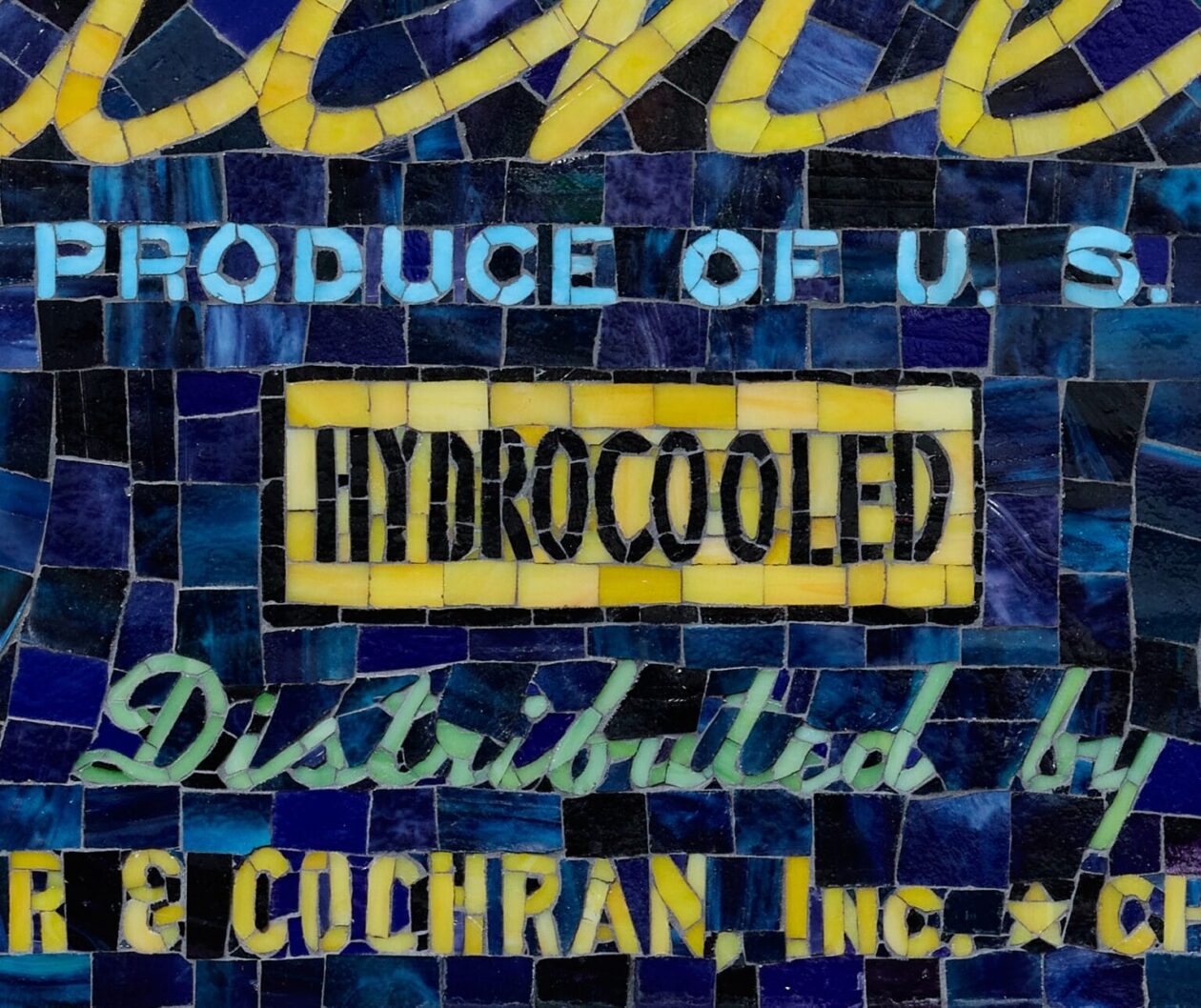

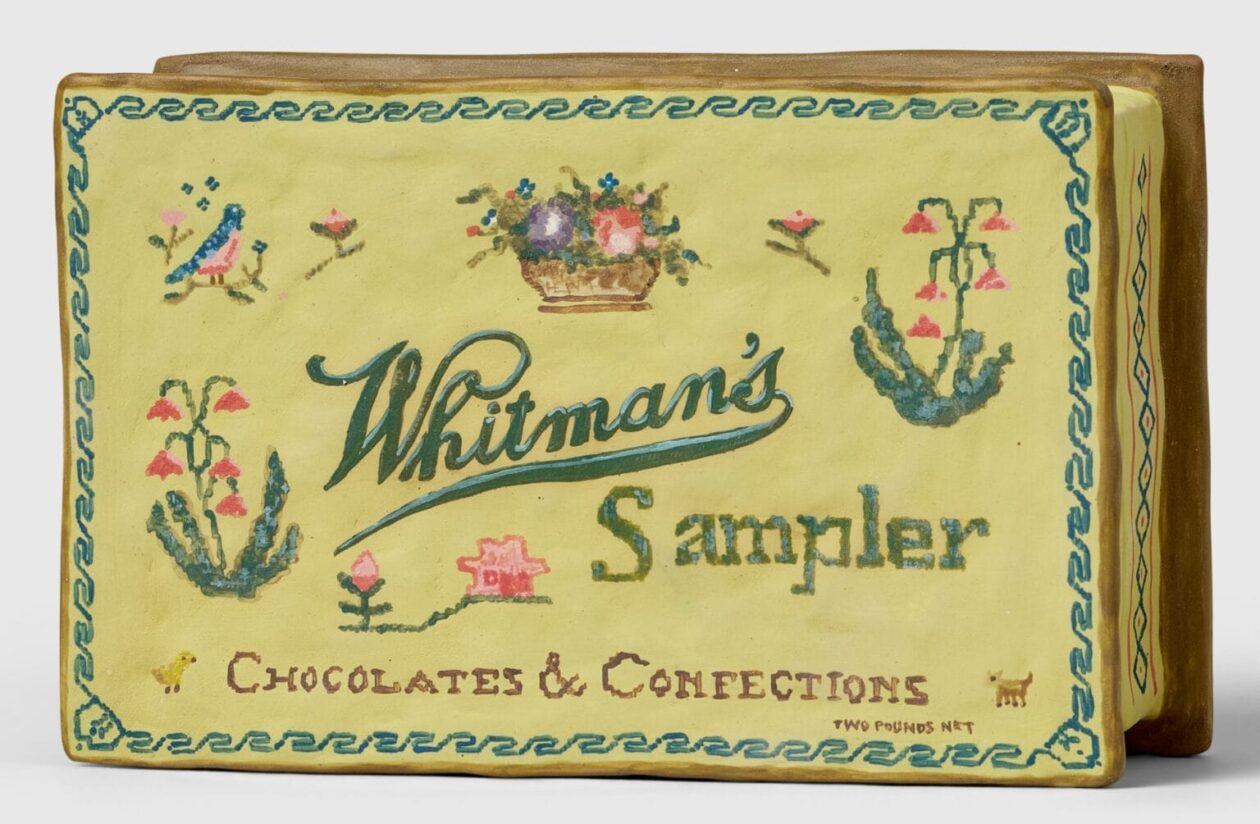

In Invisible Hand, her solo show at SOCO Gallery, Shih pairs this mosaic practice with her signature ceramic works. A stained-glass style advertisement piece titled Carolina’s Pride Peaches depicts a woman enthralled by ripe fruit — even as the story behind the harvesting labor remains unspoken. She juxtaposes that with items like ceramic replicas of Tropicana cartons, Smucker’s jelly jars, and fast-food packaging. These familiar objects often prompt questions about who produces necessities, who consumes, and whose labor is overlooked.

Shih’s work is deeply rooted in the context of immigration, exclusion, and labor. For example, Toy Building reimagines a historic location in Milwaukee once owned by a Chinese immigrant, a site that housed a restaurant, dance hall, and various businesses. Shih also references the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, legislation that barred Chinese immigration, particularly of people likely to fill low-wage roles. Through her mosaics and mixed media, she draws connections between those past legal structures and present-day policies and practices.

In combining archaeological fragments, vintage and contemporary objects, stained glass, and ceramic elements, Shih constructs mosaics that are visually sumptuous but also politically resonant. Her pieces ask us to look beyond surface beauty — to trace origins of materials, stories of migration, and systems of labor that underpin consumption. By reconnecting fragmented histories, she reveals how domestic life, commodity, and cultural memory are entangled. Visitors to these exhibitions come away not only with aesthetic impressions but also with greater awareness of whose hands have shaped the very objects we take for granted.

Those interested in experiencing Shih’s work in person can see Invisible Hand from September 18 to November 8 in Charlotte. Her piece “Toy Building (1915–1939)” is also on display as part of the exhibition A Beautiful Experience: The Midwest Grotto Tradition at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan through May 10, 2026.

More info: Website, Instagram (h/t: Colossal).

in Bahia.

in Bahia.